There’s a second half to CCR §I.iii that takes up the distinction between canonical and apocryphal books. The former are those that have been accepted everywhere, always, and by all the church as theopneustos (God-breathed) because, as Barclay put it, “no one could stop them.” But what about those that were “less evident[ly]… from the Holy Spirit”? Here’s Zanchi’s answer:

The other books, although they are contained within a volume of the holy books [in volumine sacrorum bibliorum], she nevertheless calls Apocryphal, because it is less evident that they are from the Holy Spirit than the other ones.

Girolamo Zanchi, Confession of the Christian Religion, §I.iii

This is a bit of a surprise to me. Zanchi’s rationale for calling books like Judith, Tobit, and Ecclesiasticus [sic] apocryphal is not that they are heretical or confusing or came later than the canonical OT books. Instead, he highlights that it is “less evident” to the church that they are theopneustos. Well, the Western Roman and Eastern Orthodox Churches would disagree, I suppose. But Zanchi has the rabbis on his side as well as Jesus and the apostles, who never quote from or paraphrase apocryphal books.

It turns out that it was not unusual for Reformation and post-Reformation Protestants to have a high opinion of the Apocrypha even as they distinguished it from the biblical canon. In taking this approach, they followed the Church Father Jerome (c. 342-420), who drew a line between OT canonical books and ecclesiastical books, the latter being apocryphal. (This article by David Briones is useful here.)

So, in one sense, Zanchi isn’t doing anything unusual. He likes the Apocrypha but knows that it’s not canon. Although he gives the apocryphal books “the first place after the canonical books,” he confesses that we should “use only the canonical books for proving the tenets of the faith” (§I.iv-v). Even Zanchi’s assertion that, after a point of faith has been proven from Scripture, apocryphal texts “have no little authority” as subordinate and confirming authorities (§I.v) can fit within this approach.

Yet Zanchi sure seems to go beyond saying that apocryphal books are beneficial, holding out the possibility that they are, in fact, theopneustos. It’s just that their Spirit-breathed character was “less evident” to the church, which therefore did not recognize them as Scripture. In other words, as Barclay might have put it, these books could be stopped.

So can revelation be the very word of God but not be canonical Scripture? Well, yes, depending on how we use “canonical.” Francis Turretin gives a bit more clarity when he explains an Augustinian distinction:

For [Augustine] makes two orders of canonicals: the first of those which are received by all the churches [“the canon of faith”] and were never called in question; the second of those which are admitted only by some [“the canon of ecclesiastical reading”] and were usually read from the pulpit. He holds that the latter are not to be valued as rightly as the former and have far less authority.

Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, I:104 (2T, Q9.VII)

Can revelation be God-breathed but not canonical in the narrower sense? Well, maybe. This is probably the case with Paul’s letter to the Laodiceans (Col. 4:16) or the Book of the Wars of the Lord (Num. 21:14), both of which are lost, which clearly indicates to us that the Lord determined that whatever those books contained was not necessary information for the salvation and flourishing of the entire church. The “canon of faith” was complete without them.

But here Zanchi (and Turretin) is speaking of books that we still possess. His point is that the very fact that God’s people have not always and everywhere discerned them as God’s word demonstrates that they are not canonical in Turretin’s narrower sense, even if they may be theopneustos and canonical in Turretin’s wider sense..

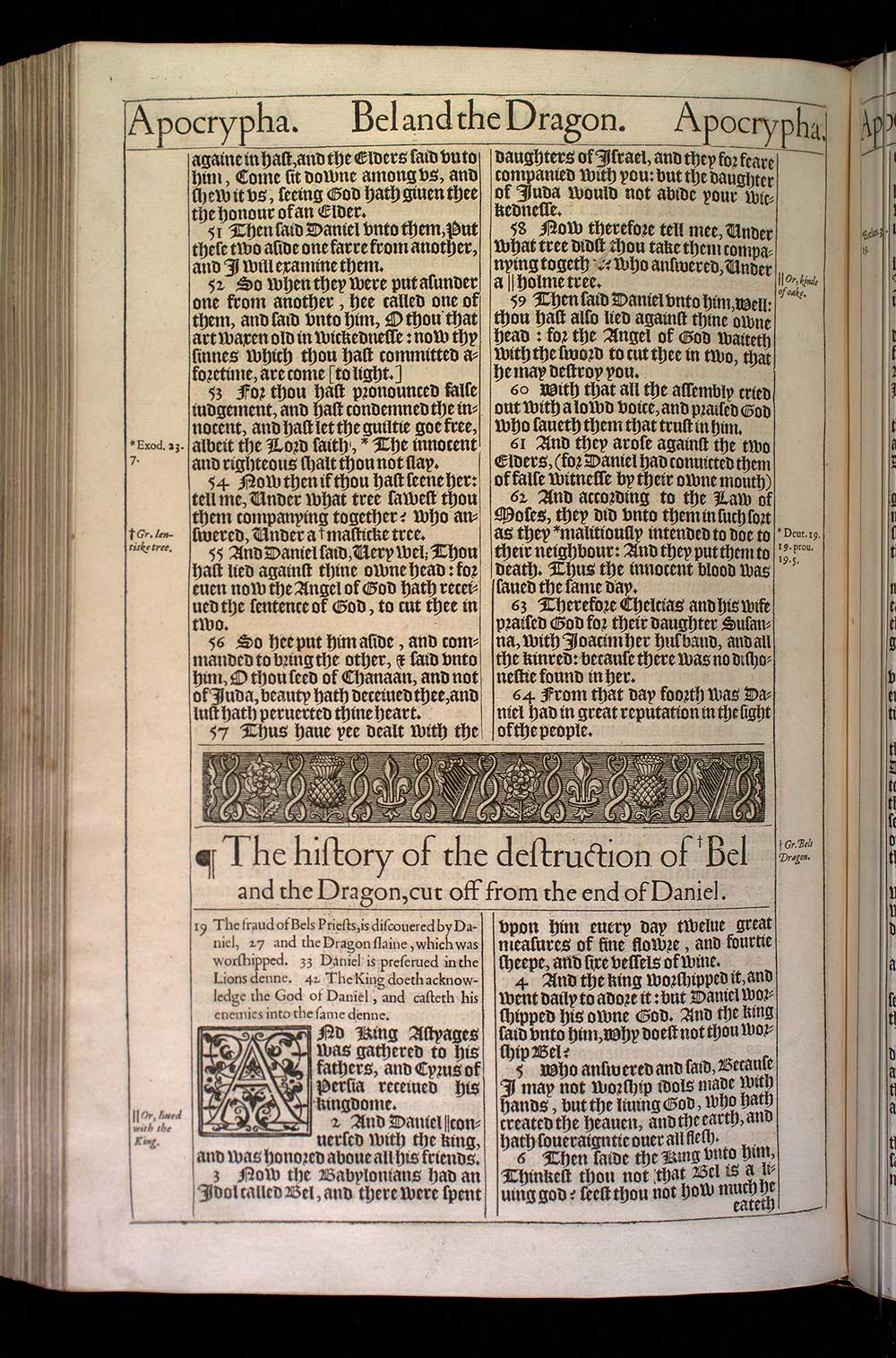

There are some things about this approach that are helpful. For example, it makes sense of why some early congregations accepted The Shepherd of Hermas or the Didache as special revelation even though the whole church never received them as canonical. But this is a difficult road to walk—Danger on all sides!—because the church has not always been content with the 66-book canon that we receive. How do we know that we aren’t missing the canonical boat by labeling Bel and the Dragon merely as apocryphal?

“How do we know?” So many of our questions come back to that issue of certainty. It’s the curse of the Enlightenment and its post-modern grandchild at work. Zanchi wasn’t unaware of the need to address this question but he also wasn’t obsessed with it in the way that we tend to be. How did he know that Bel and the Dragon was “out”? God’s OT church hadn’t recognized it. Jesus and the Apostles did recognize it. The post-apostolic church had doubts about it. It didn’t sound like Scripture. It didn’t claim to be the word of God. All this didn’t make the Apocrypha bad or useless. It just made it non-canonical.